The history of Norland in 13 objects: Great War testimonial books

11 November 2022

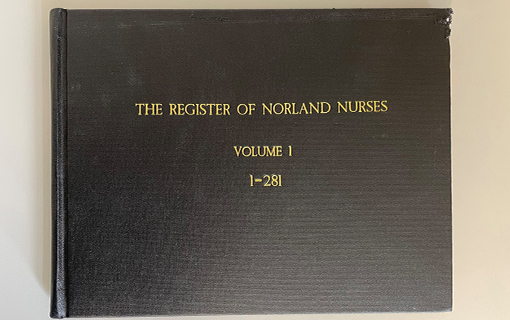

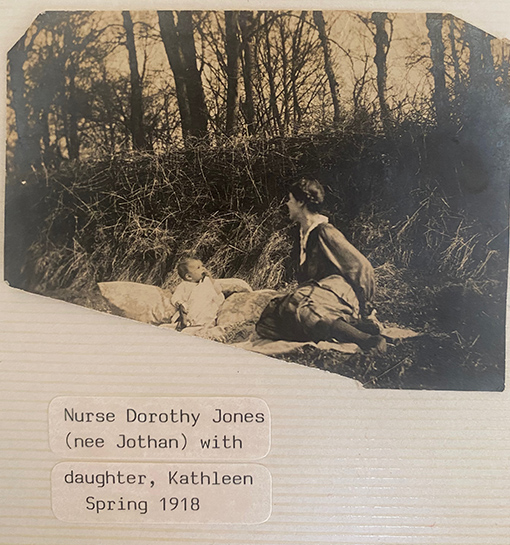

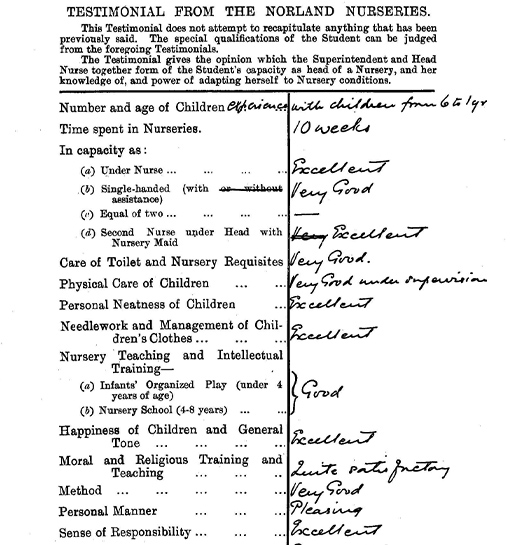

The sixth object in our series celebrating Norland’s 130-year history is a collection of testimonial books documenting Norland nurse careers during the Great War. The books offer an invaluable insight into how Norland nurses contributed to the war effort – from helping children fleeing war-torn countries to volunteering in hospitals and caring for soldiers injured on the battlefield.

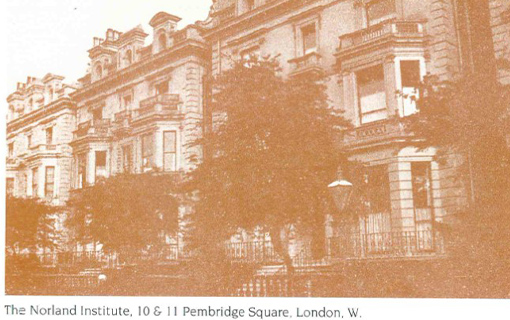

The Great War (1914-18) permeated all aspects of British life from its beginning to years after the signing of the armistice. The Norland Institute, at the time situated at 10 Pembridge Square in London, was by no means an exception. When war began, Norland was spearheaded by founder Emily Ward and Principal Isobel Sharman.

The Norland Institute was then home both to an early years training college and nurseries for young children. When war was declared, the needs of the masses became quickly apparent. The lives of children were greatly affected by the atrocities of war and Norland was in a prime position to lend a hand. The in-house workrooms, previously used to make uniforms, were quickly transformed to make baby clothes for destitute families and refugees. Another immediate measure was a drive for Norlanders to donate to relief funds. By June 1915, the Norland Quarterly newsletter revealed the Institute had donated £106, 2s and 9d to Belgian relief funds, the Red Cross and to fund beds in the purpose-built King George’s hospital, which cared for injured soldiers upon their return to the UK from 1915 until 1919.

Throughout Europe, families were displaced by war. Emily Ward’s sense of duty, which she instilled in Norlanders, quickly came to the fore. In August 1914 the War Refugee Committee was set up, to which Emily Ward pitched her coastal Sussex home, Little Hallards Estate, as a haven for shellshocked families. Her proposition was initially rejected. Undeterred, she sent a high-powered representative to petition the committee directly, and soon Belgian refugees were welcomed into the farmhouse on her property. Emily also secured jobs for female refugees as domestic servants with local families, so they could have a steady income and begin to regain their independence.

The Belgian refugees arrived very weakened from their war-torn country. One refugee boy developed scarlet fever, a highly contagious disease which at the time killed one in twenty who caught it. He had been at Little Hallards for only three days. Eventually, all the Belgian children caught the fever, putting the students at Norland who were instructed to care for the children, under immense pressure. Thankfully, all children made a full and quick recovery, testament to the expert care of Emily Ward and her nurses.

In opening her home for the war effort, Emily Ward set the standard for Norlanders all over the world as the war went on. Many probationers chose to interrupt their training to support the war effort. Others were forced to disperse from 10 Pembridge Square to take up roles abandoned by those fighting on the front line, especially after the passing of the 1916 Military Service Act. There was significant demand for manufacturing and agricultural roles. Many Norlanders worked in canteens and hospitals and other essential work. Given their hospital training, a considerable number joined the Red Cross Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD), a women-only group that went to hospitals to care for sick and injured returning soldiers.

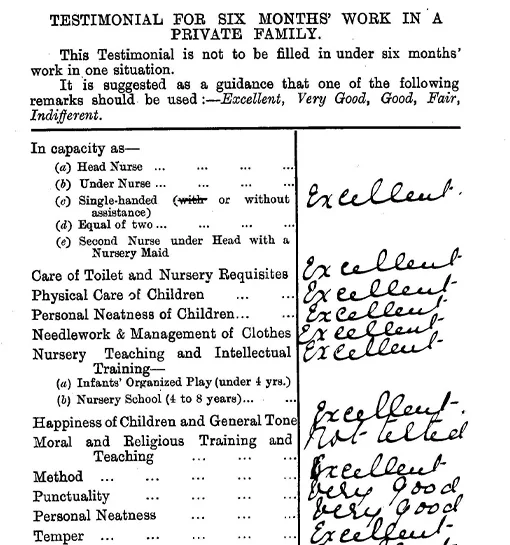

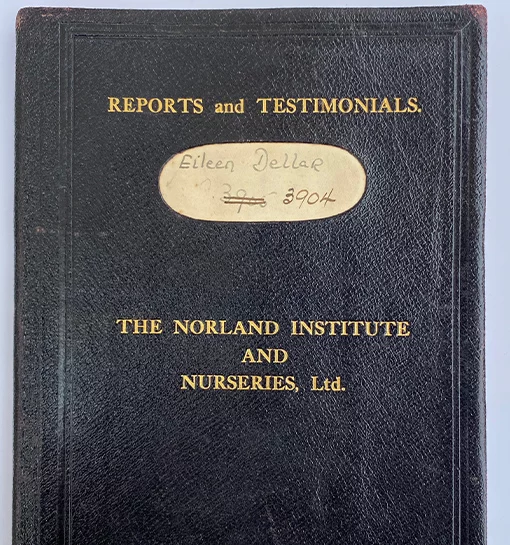

Norland is lucky to house several testimonial books in its archives. These not only contain the training certificates and report cards of each Norland nurse, but references from the nurse’s employers. During the war years, several nurses took up temporary roles, such as Nurse Mabel Lister. Mabel’s testimonial books document over fifty glowing references through her career as a Norland nurse, with five positions undertaken between 1914 and 1915. Some postings were filled for as little as two weeks, including with a family who had come over to England from India. Her little charge had great difficulties adjusting to his new life but within two weeks he was “as happy as can be”.

Mrs Peacey, Norland’s secretary during the war years, later writes that Nurse Mabel Lister took an interruption in 1915 until 1917 to join the VAD, where she worked caring for injured returning soldiers in two hospitals and received a certificate from the British Red Cross for her dutiful service. Ever in the spirit of care and compassion, Mabel then cared for her sister for several years. Her testimonial book shows the unwavering dedication of the Norland nurse.

Nurse Emma Holland left to take up a more permanent role within the VAD in October 1914. She had previously trained as a nurse before her career change to nursery nurse. She volunteered part time with the VAD from its infancy in 1909, so when war was declared she was quick to lend her expertise. Writing back to Norland in November 1914, she described her role as a “surgery probationer on the woman’s side”, eventually going on to work in a convalescent home for soldiers until the war ended.

Principal Isobel Sharman encouraged Norlanders to join organisations such as the VAD. “You have to realise it and to use your opportunity”, she reminded nurses who reported feelings of guilt for neglecting their Norland training. She was keen to maintain Norland’s ethos of strength, love and duty, and realised it was better served outside of 10 Pembridge Square. Now was the time to give their support for the good of the country.

At the outbreak of war, some nurses were quick to go to the front lines to help their comrades in battle. In 1914, of the 500 nurses situated across mainland Europe, around one in ten had been trained at Norland. Towards the end of the war, the number of Norlanders working as nurses on Europe’s battlefields reached 200, as many realised their training could be adapted to care for adults as well as children. This figure is a true testament to the strength and ardour of the Norland nurse.

This almost inevitable dispersal of Norland nurses, and the demand for young women to join the war effort, meant that applications for Norland declined during the war. By Christmas 1915, Principal Isobel Sharman recognised that “giving up their special career during the war” was unavoidable and Norlanders would eventually return. Yet, without the consistent income of tuition fees, Norland was forced to make sacrifices. The Norland Club (established in 1913 at 7 Pembridge Square), which was the home of Norland social gatherings, was given up to the war effort. Walter Ward, Emily’s husband, supplied the Institute with several loans to maintain the same high standard of teaching and care for the children who remained in the nursery. Norland’s reputation as the best in its field ensured its future. Throughout the war, the Norland Institute still registered on average 700 active nursery nurses and students each year.

Even through the chaos of war, Norland remained steadfast, living up to its motto ‘Fortis in Arduis’ (‘Strength in Adversity’). Emily Ward and Isobel Sharman adapted their methods to best suit the insecurity and hardship of living in such times.

As the economy crashed, many nurses found their families could no longer afford to keep them on. In the Norland Quarterly, during the dismal Christmas of 1914, Sharman wrote that “some Norlanders have lost their situations through circumstances caused by the war and is entirely beyond the control of the individual nurse”. The war also put a virtual end to work on the continent. As the lines between battlefield and civilian life blurred, it became unsafe for many nursery nurses to continue in their posts. Many nurses, themselves only in their late teens or early twenties, were forced to decide between returning to England or abandoning the charges they loved.

Nurse Grace Taylor, who worked for the countess de Borchgrave in Brussels, took her charge back to England with her to care for him in her own home until the war was over and he could be safely returned to his family.

1917 saw Nurse Marion Burgess, who worked for the Grand Duchess Kiril of Russia, flee the palace alongside her employers and three charges. As members of the Russian aristocracy, Marian’s employers were exiled to Poland in the first years of the Russian Revolution. Burgess’ obituary in the June 1920 Quarterly states “it was six years since Nurse Burgess had a holiday, and when she might have come in 1918, she would not leave her post of duty while her employers were having such anxious times”. Weakened and starving through exile, Marion died in 1920 after contracting influenza while nursing her small charges through the illness to full recovery.

The uncertainty was calmed by Isobel Sharman in her regular Norland Quarterly letter. “We have heard that they are ‘safe and well’”, she wrote to the peers of nurses in Europe, who were concerned at the lack of contact. Norland reached out to Norlanders overseas as much as possible, providing them with care and support through tempestuous times.

Principal Sharman (left) personified Norland’s values. ‘Love Never Faileth’ remained her motto throughout her life. Her calming letter in the Christmas Quarterly of 1914 encouraged kindness towards Germans, as opposed to hatred, at a time where xenophobia was rippling through Britain as the public realised the war was not going to end soon and British lives began to be lost. She encouraged Norlanders to “tackle the spirit of hatred… looking forward to the fact that the babies in the nursery today will, we hope, be friends with the present German babies.” Sharman was determined that, no matter what was going on throughout the world, the spirit of Norland was upheld and that love be extended to German and English families alike.

Isobel Sharman encouraged nannies not to hide the existence of war from their charges. “I totally disagree with the idea that the children should be kept in ignorance of the war,” she wrote, noting that future generations could benefit from learning from the mistakes of their predecessors, and that excluding them from history was counterproductive. Aware that many of her students’ charges would grow up to be future world leaders, she encouraged Norlanders to raise their charges in the spirit of love and affection, and sow the seeds of a kinder future.

After being diagnosed with inoperable cancer, Isobel Sharman (whom Emily Ward knew affectionately as ‘Bella’) passed away on 11 January 1917, amid the Great War. Her legacy remains; the spirit of kindness and affection in the face of hardship very much still present in the Norland community today. After Isobel’s death, Emily Ward took on the role of Principal assisted by Vice Principal Jessie Dawber, who had been working at Norland since before the war.

By the end of the war, Emily Ward’s focus was on the financial struggles of Norland. With many nurses working elsewhere, assisting their families or no longer able to afford their tuition, and many graduates choosing to pursue different career options after the war, income had declined. She was forced to sublet the building. Ward urged Norlanders to “tell me whether you intend to support the institute or whether you feel that you would rather work as isolated, independent units.”

A legion of devoted Norlanders and clients begged Emily Ward not to abandon Norland. The winter of 1918 was spent responding to their suggestions for its future existence in a post-war world, including the addition of a pension fund and prospects of post-qualification training.

Although finances were tight, demand for Norlanders remained high. During the war, the need for temporary nurses increased extensively. Even until early 1919, there were between 40 and 50 daily requests for nurses. Even though Norland had struggled in the war economy, the desire for its graduates remained unwavering, as did the number of nurses on the Norland roster despite the uncertainty. At the beginning of the war, 576 nurses were listed on the Norland books, by Christmas 1921 there were 573.

What becomes apparent about Norland during the Great War is the unwavering dedication of the Norland community to its founding mottoes ‘Strength in Adversity’ and ‘Love Never Faileth.’ Every act undertaken, every decision made, was underpinned by these values, which continue today. The extensive efforts of Norlanders, students, and staff to support their communities and families during the COVID-19 pandemic is testament to the Norland spirit established by Emily Ward and Isobel Sharman (right) all those years ago. Then, as now, Norland training equips its graduates for almost anything, while also fostering professionalism, respect, commitment and love for the children in their care and the families they work with.