The history of Norland in 13 objects: Emily Ward's diary

5 April 2023

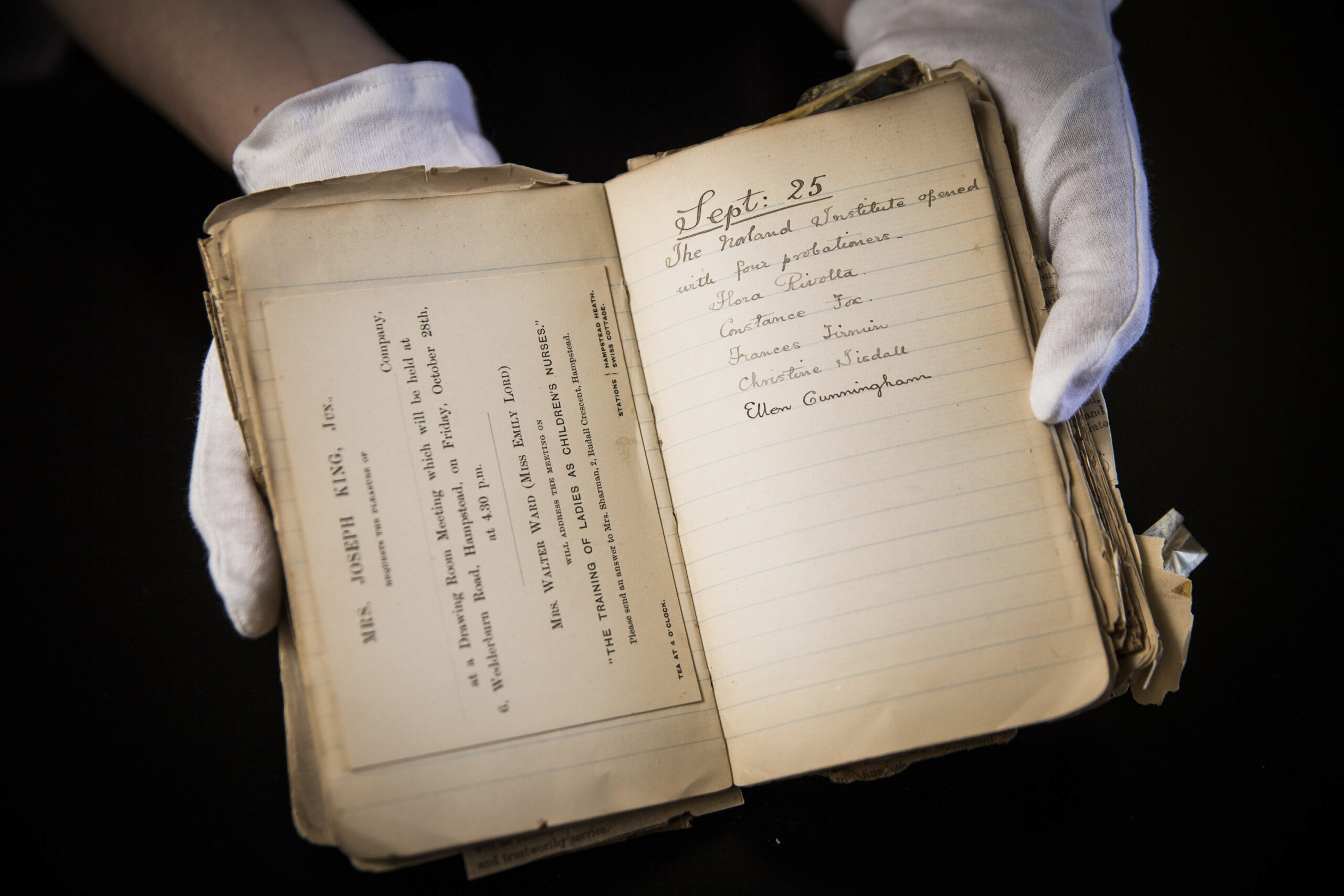

The 13th and final object in our series celebrating the rich 130-year history of Norland is founder Emily Ward’s diary from 1892.

On 25 September 1892, Emily established the Norland Institute at 9 Norland Place in London. In doing so, she recognised the need for early years childcare to be more structured, centred around the child, loving and nurturing. Her notebook documenting the months ahead of Norland’s opening and its first years was discovered by Events Manager and Norlander Elizabeth Harvey in 2017.

Emily Ward’s notebook had been missing for almost 100 years when it was discovered in the archives by Elizabeth Harvey in 2017. The black, leather-bound book contains over 120 pages of first-hand accounts of the founding days of Norland. Mrs Ward filled its pages with newspaper cuttings, invitations, meeting notes and documents from 14 May 1892 all the way to 6 November 1919. Emily’s handwritten notes contain personal insights, challenges and reflections that accompanied her journey to creating a new career path: the professional nanny.

This notebook, which acted both as a diary and training manual, offers a key insight into the process Emily Ward went through to establish the Norland Institute. She started by jotting down a list of “associates” – respected society women who were willing to provide accommodation for students or lend their skills in the teaching of subjects such as needlework or physiology. She also wrote a list of prospective clients, keen to secure a Norland-trained nursery nurse – despite no students yet having earned Norland certification. The high demand for fully-qualified Norland graduates is something that continues today – for every Norlander seeking work through Norland’s dedicated in-house agency, there are on average around seven jobs for them to choose from.

Emily Ward’s notebook documents four pages of families interested in hiring a Norland student. There were just five probationers enrolled when the Institute opened: Flora Rivolla, Constance Fox, Frances Firmin, Christine Tisdall and Ellen Cummingham. This number very quickly grew. By 1893, there were 46 members of the Norland Institute.

Momentum for Emily Ward’s vision was there from the beginning. Mrs Ward often hosted “drawing room meetings” in the early stages of Norland’s conception. During these meetings, influential members of London society would gather to listen to Emily Ward’s ideas about the importance of professionalised home-based childcare, and how Norland could be the driving force for this. The innovative nature of Norland generated an exceptional level of press coverage. A cutting from The Woman’s Signal in 1894 said: “The Norland Institute has come, and is going to stay, as the pioneer for happy, healthy, childhood.” By 1894 the Nursing Record publication details that the Norland Institute is now firmly established and much valued both by those trained and the families who employ them.

These cuttings, notes and more were only discovered during Norland’s 125th anniversary celebrations in 2017. The fragile pages of the notebook went largely unnoticed for almost 100 years.

“During the move from Denford Park to Bath in 2003, we really only had a few days to pack up and go,” says Norlander Elizabeth Harvey. “I was packing up the library and found a stack of old, tatty-looking books, which some believed had no place in a new modern library, as we were undertaking a cull of old books, but I decided to take them home”.

Elizabeth trained with Set 75 and continued to work in various roles within Norland throughout her career – from the Norland Nursery School at Denford Park to Placement Facilitator. Elizabeth also delivers diploma classes and wrote and managed the Early Years BTEC course, which Norland consulted on for schools and further education colleges. Her most recent role involves organising the graduation ceremonies for the Norland-awarded early childhood degree and prestigious diploma, alongside organising the value-added curriculum of workshops and guest speakers.

Elizabeth’s decision to take the stack of books home with her was possibly the greatest decision she could have made, as it would provide an insight into Norland’s history that had never before been accessed. Elizabeth was unaware that she would be the custodian of the notebook for over a decade when she offered to keep boxes of old Norland documentation at her house during the move. It was almost 15 years later when she decided to have a clear-out in her home and realised what she had found. “I just had the inclination to look at the book and instantly felt butterflies – it was so special! As soon as I opened the first page and saw the handwriting and the date 1892, I thought: “oh my goodness, this is Emily Ward’s notebook. I gently packaged up the book and brought it into the college for the team to see.”

Principal Dr Janet Rose, on the discovery of the notebook, said “we cannot underestimate the importance of this notebook and of the role Emily Ward played in recognising the value of having a qualified, highly trained professional, looking after children. Emily sought to, and succeeded in, professionalising the role and made the nanny a valued and highly regarded career for women, and men, for generations to come. This notebook gives us a unique insight into Emily’s challenges and thoughts at the time she was embarking on such an ambitious and revolutionary project.”

In creating the Norland Institute, Emily Ward pioneered the professionalisation of early years education and care. Prior to the introduction of formal training at Norland, children would be cared for by untutored housemaids. With the establishment of the world’s first formal training centre for nursery nurses, Emily created the training model on which all future nursery nurse training would be based.

“Some considered it retrograde, whilst others thought that we should have difficulty in persuading girls, who had received High School education, to take up what they called ‘menial work’. I must, however, acknowledge that some have since fully recognised the value and importance of careful nursery training, as foundation for the further development of the child at school.” (First Report of the Norland Institute, 1895).

“I look forward confidently and hopefully to the time when a nursery nurse will command from the public the same amount of affection, respect, and trust as is now universally accorded to the hospital nurse and the trained teacher.” Emily Ward had established the early years profession, just a few years after Florence Nightingale founded the first nurse training school at St Thomas’ Hospital in 1860.

In her notebook, Mrs Ward wrote that it was her wish “to form a new occupation for young women whose circumstances do not enable them to undergo the long course of professional training essential to a successful educational career even when they are endowed with sufficiently intellectual abilities. Study includes Needlework, Hygiene, Froebelian instruction and Hospital teaching.”

Emily Ward, much like Florence Nightingale, recognised the need for reform and fought to achieve it in a world where pioneering women were often shunned to the sidelines. Thanks to Nightingale’s efforts, nursing was no longer frowned upon by the upper classes; it had, in fact, come to be viewed as an honourable vocation. Emily Ward was able to evolve public perception in a similar way – her early entrants were considered “gentlewomen”, recruited by personal recommendation, who had a genuine passion for providing the best-quality care for children.

Early training programmes, which Emily describes at great length in her notebook, included a rigorous three-month residential with six weeks in kindergarten settings. Students wishing to enrol at the Norland Institute were subject to aptitude tests. In 1955, Nurse Marion Read recalled her 1900 entrance exam as being one of general knowledge and remembers “how lucky it was that the making of marmalade should be one of the questions” as she had made some only the week before. However, other questions such as the locations of popular London streets and shops left her bewildered, as she had travelled from the country to attend Norland.

When students were accepted to the Norland Institute, they paid £36 for the three-month course, which is the equivalent to the purchasing power of just under £6,000 today. Students spent three months in residential training, where they spent successive fortnights specialising in cookery, laundry, and various other household chores. These practical classes would run until noon and, true to Froebelian tradition, afternoons were spent in lectures, on kindergarten games, walks and needlework, to name but a few of Emily Ward’s varied activities. After an intensive three months, students were placed within the kindergarten department of a local school for six weeks, culminating in their final three months in a placement on a hospital children’s ward. For Emily Ward, this placement was especially important as “a nurse should gain an insight into the life and struggles of the poor. Her outlook on life is enlarged and her sympathies widened”. Mrs Ward’s philosophy was that it was the duty of the “well-born” to care for the poor.

The syllabus was extended and modified in 1903, which brought tuition fees up to £66 (about £10,270 today). Kindergarten experience became three months long and probationers returned to Norland after their hospital placement for another three months of lectures and practical, domestic classes. Mrs Ward also made the decision to defer certification until students had completed six months of satisfactory work within a probationary post – laying the foundations for today’s Newly Qualified Nanny (NQN) year, in which students complete a full-time placement year in paid employment with a family.

Emily Ward’s pioneering vision remains central to Norland’s culture and ethos today, over 130 years later. In her address to the Norland Institute’s fourth badge presentation in June 1911, she told her students and Norlanders that her aim was to “show that the care of little children and nursery work was not primarily menial but educational”.

Through this series, exploring Norland’s groundbreaking history through 13 objects from the archives, we have unpacked how Norland has come to be what it is today: a leading higher education provider dedicated to cultivating exceptional professional early years practitioners. Norland’s unique blend of academic and practical training and lifelong careers and professional development support stands as a true testament to Emily Ward’s pioneering vision over 130 years ago.