Presenting frameworks for early learning, development and care in an intergenerational care village – position paper

Back to Norland Educare Research Journal

About the journal

Read more about the journalEditorial board

View our editorial boardJournal policies and ethics

View our policies and ethicsPeer review process

View peer review processInformation for readers

Read our information for readersInformation for authors

Read our information for authorsCall for papers

View our call for papersTerms and conditions

View terms and conditionsAbstract

Intergenerational practices are not new yet are growing in popularity worldwide (Fitzpatrick and Halpenny, 2022) in a variety of forms. The benefits of connections between older adults and young children are emerging (Heslop, 2019), yet guiding frameworks for practice are lacking. This paper focuses on the concept of integrated intergenerational educare and offers an example of children in their early years working and playing alongside non-familial older adults who are resident in an intergenerational village in the north of England. The children, aged from birth to five years, attend a charity-led, Ofsted-registered day nursery within the village. Drawing on data from engagement in prior research (Heslop and Caes, under review), and from wider reading, the authors learned of the motivations, expectations, rationalities and experiences of early education and adult social care providers and set out to develop and present a new framework for intergenerational educare. Two innovative intergenerational frameworks, the Attuned Relationships Model and the Mirrored Curriculum Framework, which align to the Early Years Foundation Stage and mirror the needs of older adults, are presented. The development of the frameworks is discussed, key aspects of the frameworks are outlined, and practical implications for practice and research are shared.

Keywords: early years care and education, intergenerational, early years pedagogy, leadership, relational transformation

Introduction

Gawande (2014) argued for the opening up rather than the narrowing in of thinking about how we provide care. He was referring specifically to end-of-life care as his father approached death, but his arguments apply to all forms and stages of care and equally education.

Modernisation did not demote the elderly. It demoted the family. It gave people – the young and the old – a way of life with more liberty and control, including the liberty to be less beholden to other generations. The veneration of elders may be gone, but not because it has been replaced by veneration of youth. It has been replaced by veneration of the independent self. (Gawande, 2014, p. 44)

Worldwide, professionals from health, social care and education are recognising the potential of bringing generations together through intergenerational practices that include a new vision for early years education and care as well as older people’s care. This multi-professional interest stems from a range of shifting factors which require fresh thinking around the increasingly urgent issues of a rapidly ageing demographic alongside the economic, societal, cultural, ecological and wellbeing challenges facing families, especially those with preschool children. The costs of high-quality childcare and older people’s care are prohibitive to many, affecting access to training and work opportunities for increasing numbers of individuals with caring responsibilities, many of whom live in the most marginalised communities.

Marmot et al. (2020) offered the most comprehensive overview of the complex, interrelated issues affecting the population, examining progress in addressing a range of inequalities in England. Major and Briant (2023) suggested that three key objectives in the Marmot study specifically relate to the rationale for early years care and education models that increasingly feature intergenerational work: giving every child the best start in life; enabling people to maximise their capabilities and have control over their lives; and creating and developing healthy and sustainable places and communities (Major and Briant, 2023, p. 4).

Crisp (2020) extended thinking in these areas. He argued for the opening up of new ideas about health creation and quality of life, suggesting that this requires fresh approaches that do not layer more initiatives on already failing services. He also explored issues of power and control, suggesting that professionals do not create health – we all have individual responsibility for ourselves:

All of us as individuals have responsibilities for our own health and often for the health of our families. Our behaviour, diet, exercise and use of tobacco and alcohol all affect our health and wellbeing. And employers, educators, architects, businesses and community leaders, as well as government, also have a responsibility to create the conditions that allow us to live healthy lives. (Crisp, 2020, p. 4)

More recently, there has been much discussion about the provision of early education and childcare in the UK and globally. A report published by the Women’s Budget Group (2021) outlined five key challenges facing the UK. The UK Women’s Budget Group is a feminist economics think tank, providing evidence and capacity-building on women’s economic position and proposing policy alternatives for a gender-equal economy. The five challenges highlighted were unaffordability, unavailability, underfunding, the staff retention and recruitment crisis, and the impact on women’s careers and the wider economy (The UK Women’s Budget Group, 2021, p. 2).

These represent long-standing concerns but, when considered alongside post-Covid anxieties about the development and wellbeing of babies and young children, suggest the need for increased urgency and action to re-energise the political and societal interest in the importance of early education and care (UK Parliament, 2021; Mulholland, 2022; Ofsted, 2022; Fazackerley, 2023).

It appears that the number of children arriving in school below the government’s prescribed developmental levels and therefore considered not to be ‘school ready’ is proving a stubborn statistic to shift. Over 1,000 teachers surveyed by Kindred Squared (2023) assessed that 46% of children in reception classes were not developmentally ready to transition to school. The concept of school readiness is contentious among early years experts, who consider the persistent focus on the meeting of prescribed standards to disregard children’s need to play and have time to develop at their own pace. Concerns are also apparent in the world of adult social care, where contributory factors such as workforce shortages, poor morale and inadequate training are affecting the capacity to provide high-quality person-centred care (Kings Fund, 2019; NHS Confederation, 2023; Local Government Association, 2020).

However, despite all these reports about the need to invest in early years provision, the modes of delivery, particularly for government-funded settings, remain traditional and unchanged – for example, the discrepancies between maintained nursery school funding and funding allocations to the non-maintained childcare sector. Workforce pay is low, with conditions of employment often poor. Many early years and childcare providers are struggling to maintain their businesses in this austere economic environment, and some appear emphatically consumed with competitive, target-led approaches that prioritise attainment and standards measures (Ofsted, 2022) above personalised developmental needs and holistic wellbeing. Such an operational backdrop places tremendous pressure on parents and providers to ensure the effective delivery of the Early Years Foundation Stage framework (Department for Education, 2023) and associated Birth to 5 Matters guidance (Early Years Coalition, 2021). In the weakest settings, this may result in children being robbed of the genuine learning opportunities and time for unstructured play and unfettered exploration which are so critical to healthy brain and body development.

Furthermore, as we continue to see austerity affect the lives of a growing number of families and children (Child Poverty Action Group, 2017; 2020) and currently face a future where over 22% of the population of England will be aged over 65 years by 2032 (Centre for Ageing Better, 2022), it is increasingly important to include considerations of equity and inclusion. These sit within the context of a lifelong health and wellbeing approach that is continuous and encourages resilience and self-determination.

Across the UK, public sector care and education services for both young children and older people continue to face significant budgetary and recruitment/retention pressures. Between September 2022 and September 2023, the National Day Nurseries Association (2023) documented 216 nursery closures across England, representing a 50% rise compared with the previous year. According to adult social care figures from CSI Market Intelligence (2022), over the 2021–22 year, 247 care homes closed in England, representing a 2.6% overall market decrease in provision.

In response, other countries have already made a shift to encompass and develop intergenerational learning and care models, understanding that a thriving ecosystem of any sort requires harmony and collaboration. To support such developments, national bodies have become established in the USA, Australia, Scotland and Ireland, and a Global Intergenerational Week hosted by Generations Working Together (2024) is celebrated annually, bringing together more than 15 countries. Global Intergenerational Week is a campaign aimed at inspiring individuals, groups, organisations, local/national governments and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) to act coherently to connect people of all ages through intentional and impactful shared opportunities and experiences.

In America and Australia, Generations United and the Australian Institute of Intergenerational Practice, respectively, are forward-thinking organisations sharing a cohesive vision to advocate directly for federal and state policies, programmes and interventions that build intergenerational connections which meet the needs of babies, children and young and older people. Their belief is that public policy should meet the needs of all generations and that resources can be used more effectively when directed at connecting generations as opposed to separating them. Interestingly, this is a long-standing belief. Highet (1950, p. 6) asserted that “wherever there are beginners and experts, old and young, there is some kind of learning going on and some kind of teaching. We are all pupils and we are all teachers.”

In Japan, yoro shisetsu, meaning ‘facilities for children and the elderly’, were first established in 1976. Since then, various models have emerged as the national ageing demographic has shifted. The traditional culture in Japan and many other Asian countries favours multigenerational households in which grandparents are supported by their children and vice versa, with both groups sharing a family home. However, as prosperity has increased and work has expanded outside the home, more older people, particularly those living with dementia, have required additional older people’s care services. As such care facilities have developed, Japan has provided the best example of seeking to retain the culture of multigenerational living through an assets-based approach (Cassidy, 2021). This places a strong focus on what children and older people bring as assets to share with each other, valuing sustained relationships, sharing skills and genuine reciprocity.

It is within this broad international context that this paper positions the case for stepping outside the current boundaries of UK early childhood policy and practice to consider the potential of designing a dynamic local ecosystem of care around the child that includes a fresh look at family support, relational pedagogies (Cliffe and Solvason, 2023), equity (Major and Briant, 2023) and how older people can make a powerful contribution to early care and education. In particular, the aim of this paper is to present the Attuned Relationships Model (ARM) and the Mirrored Curriculum Framework (MCF) developed by Egersdorff and Ludden (2022; 2022a), which define the approach taken by the charity Ready Generations. Prior to introducing these innovations, the charity will be outlined.

Ready Generations is a national charity engaging in action research to explore the social, emotional and cognitive benefits of connecting people of different generations through meaningful experiences, invitations and opportunities. In July 2022, it opened a fully integrated intergenerational Ofsted-registered day nursery providing childcare for children aged 0–5 years in a new purpose-built care village in Chester, in partnership with Belong Villages, a care provider for older people. This followed over six years of partnership working with Belong Villages to consider the benefits of bringing early years children and older adults, many living with dementia, together on a daily basis through planned and spontaneous invitations, opportunities and experiences. The partnership is co-funded, with Belong Villages owning the nursery space, which is leased to Ready Generations. Ready Generations is the Ofsted-registered provider of early years education and care, and takes full responsibility for the employment of the early years staff team. Belong Villages employs an intergenerational lead who is responsible for supporting the coordination of the offer and ensuring the needs of the older people are fully considered.

Theoretical framework

Inspired by Bronfenbrenner (1979), and building on reading from ecological theory as well as studies conducted by two authors of this paper (Heslop, 2019; Heslop and Caes, under review), the intergenerational ways of working proposed in this paper require more structures for practice which rethink professional boundaries and offer an inclusive ecosystem that demonstrates equity for all. Considerable strength and determination from social thinkers of the past is drawn on. These include Caroline Pratt, a progressive educational reformer who wrote about the creation of her new City and Country School in New York City in 1914. She highlighted the need for first-hand experiences, open-ended materials, free play and creativity at a time when children were expected to be seen and not heard. Her vision was challenging and innovative:

The school as I envisioned it had no fixed limits, no walls. It would take shape under the children’s own hands. It would be as wide and as high as their own world, would grow as their horizons stretched. And as children make use of whatever they can find around them for their learning, so would the school. (Pratt, 1948, p. 40)

Ready Generations aims to present an equally ambitious, meaningful and impactful model of intergenerational learning and care that creates spaces for new conversations to take place and, above all, holds the belief that:

Innovation eco-systems are like rain forests rather than cropland – they thrive not because of the mere presence of assets but because of the way in which elements mix together to create new and unexpected flora and fauna. (Hwang, 2012, p. 34)

Ready Generations’ vision of intergenerational care involves the conceptualisation of a theoretical model encompassing educational and social care theory and practice. It also draws on empirically supported and evidence-based reports and studies, where available. Furthermore, the model assumes commitment to the continuing research and evaluation of intergenerational care and education that aims to both test and improve delivery models. Ultimately, however, this work and research reflects a commitment to the efficacy of intergenerational care that is value and relationally based.

Methodology

Three main stages contributed to the development of the ARM and the MCF. Firstly, underpinning everything came decades of professional learning, practice and leadership within early years. Egersdorff, Ludden and Heslop are qualified early years professionals who have experience of care training and delivery for older adults. Heslop is also an academic and, along with Caes, undertakes research with Ready Generations.

Secondly, a literature review of intergenerational practice and research, undertaken initially by Heslop (2019) and updated by Heslop and Caes (under review), was utilised in order to identify strengths as well as gaps in practice, research and policy. Thirdly, in a spirit of continuous reflection on practice, Ready Generations colleagues consulted with stakeholders at the intergenerational village at the time of their first anniversary and reported in the charity’s first impact report (Ready Generations, 2023). This was an everyday evaluation of provision that commonly occurs in the care sector during provision and training.

All monitoring and evaluation processes were developed using the Ofsted Early Years Inspection Handbook (2024), which refers to a setting’s intention, implementation and impact. For example, when making judgements about quality of education, focus was directed at what children needed to learn, how the setting was going to make this happen and, finally, the difference it made and the progress achieved by the children. Ethical principles for work-based learners (Durrant et al., 2011), including respectful working with colleagues, permeated the development of the ARM and MCF. It is crucial to claim intellectual property on the ARM and MCF before the essential next steps of evaluating their impact.

The Attuned Relationships Model (ARM) and the Mirrored Curriculum Framework (MCF)

The ARM and the MCF aim to improve the delivery, monitoring and evaluation of high-quality education and care in an early years care and education setting and as part of a test-and-learn research into intergenerational practice. In a fair, enriching society, education, care and health should be able to demonstrate their interrelated capacity to be great enhancers and levellers by enabling service users to achieve wellbeing and success regardless of their health, wealth, status, ethnicity, gender, sexuality or disability. Guided by findings from research (Heslop and Caes, under review) and wider reading, the ARM and the MCF provide structure and form to the planning and organisation of an intergenerational offer for both children and older people. Aligned with the Early Years Foundation Stage (Department for Education, 2023), they dovetail together but have their own unique purpose. The ARM and MCF will now be introduced.

The Attuned Relationships Model

Figure 1 Ready Generations’ Attuned Relationships Model (ARM) (Egersdorff and Ludden, 2022)

The ARM (Figure 1, Egersdorff and Ludden, 2022) provides the rationale and set of relational pedagogy principles that underpin the practice. The ARM is grounded in the ethical concept of human dignity at all stages of the life course from birth onwards. Its intention is to actively represent the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (United Nations, 1989), the United Nations Principles for Older Persons (United Nations, 1991) and the Human Rights Act (Equality and Human Rights Commission, 1998). As such, it has a strong emphasis on listening and treating all people equitably with fairness and dignity, whatever their age, ethnicity, ability, wellness, gender identity or life circumstance. The model recognises how we are all social creatures, driven by the need to make and find meaning through positive connections and meaningful relationships that result in shared joy, security, wellbeing and achievement. The ARM is influenced by the work of the Center on the Developing Child (2021) at Harvard University that identifies three interconnected principles for effective relational practice, based on the science of early childhood development. These principles have been adapted by Egersdorff and Ludden (2022) and applied to all Ready Generations programmes, as well as to the charity’s service design and professional development.

By applying these principles to intergenerational work and using them to support reflection, assessment and evaluation around children and older people’s wellbeing, learning and achievement, there is potential to make a real difference and to have impact that is both immediate and sustained over time.

Underpinning these operating principles is a belief that, as humans, we all actively seek out certain states of mind, personal characteristics and experiences to protect ourselves and feel that we belong and have purpose. These are defined in the MCF (see below for details) as ‘life gifts’ (Table 1), which are used to support the assessment of individual progress and next steps. The life gifts of Ward and Brown (2004), who worked in the context of offender rehabilitation, have been built on here. These promote the idea that we need to actively support people to build their unique strengths and capabilities. Achieving a balance of life gifts is fundamental to good human functioning, taking control and finding personal meaning. Intergenerational planning and practice reflect the centrality of these gifts in all learning invitations, opportunities and experiences alongside meeting the statutory requirements as set out in the Early Years Foundation Stage framework. The synergies between government expectations for children from 0 to 5 years are demonstrated in Table 1.

The ARM offers a strengths-based relational model which takes a life-course approach and integrates rather than segregates the needs of our children and older people. The aim of Ready Generations is to build everyone’s capacity and capability, whatever their age, background or stage of development. The intergenerational community should have the opportunity to engage and connect in ways that give a sense of value, purpose, confidence and motivation to experience life to the full whether an individual is at the beginning or nearing the end of life’s journey. Human flourishing should be viewed as an attainable goal for everyone. This is articulated in all strategic and operational planning and achieved through collaborative professional conversations between early years and care teams.

The intention of the ARM is to support children and older people to live well by:

- understanding themselves and what matters most to them

- recognising and expressing feelings and emotions, and understanding their potential impact

- building reciprocal, nurturing and sustained relationships over time

- managing impulse and regulating unhelpful behaviours

- feeling in control of life and having a sense of personal direction.

In addition, the intention is to help children and older people to feel safe, connected and able to express themselves in ways that make meaning and anchor experiences, as well as helping them to:

- have their needs met at a deeper level

- formulate personal goals and future aspirations

- foster independence and good choices

- solve problems and construct personalised plans

- gain and maintain a sense of freedom and autonomy

- make rich and unique contributions

- feel part of an active, nurturing community.

Table 1 Life gifts, adapted from Ward and Brown (2004)

The life gifts | Early Years Foundation Stage |

| A good life – feeling in control, having choices and being happy Inner calm – experiencing freedom from emotional upset, turmoil and stress Relatedness – feeling connected to caregivers, educators and significant others Meaning-making – making sense of the things that matter most to us Community – connecting with the local environment and our neighbours Healthy habits – making good choices and having purpose in life Joy – feeling good in the here and now Creativity – expressing individuality in uniquely personal ways Empathy – understanding and responding to the perspectives, feelings and situations of others Cognitive fitness – building and sustaining executive functioning skills, e.g., memory, attention, processing speed and problem-solving Playfulness – experiencing playfulness through imaginative and fulfilling opportunities Learning – experiencing high-quality and consistent learning opportunities including mastery experiences Personal agency and identity – feeling noticed, listened to and able to make a unique contribution | These are the prime areas of: · communication and language · physical development and wellbeing · personal, social and emotional development and wellbeing.

The further four specific areas are: · literacy · mathematics · understanding the world · expressive arts and design.

The non-statutory guidance provided through the Early Years Coalition’s (2021) characteristics of effective learning also supports learning across the ages. The three characteristics are: · playing and exploring · active learning · creating and thinking critically.

|

Through this inclusive approach to planning aligned with respectful implementation, people feel supported by committed, reflective professionals who have developed shared expertise in:

- attuning to the internal, personal world of the individual whatever their age in order to know what is important to them

- supporting communication and dialogue by modelling use of rich language that captures experiences and helps others to make sense of them, especially where that sense may not be fully accessible

- providing creative opportunities for meaning-making by scaffolding both independent and shared experiences

- building relational competencies that encourage people to take the small risks needed to enjoy rewarding relationships and experiences

- understanding the importance of psychological safety, including recognising and responding to barriers that might get in the way of full engagement.

Following the creation of the ARM, the founders of Ready Generations progressed with design of the Mirrored Curriculum Framework (MCF)

The Mirrored Curriculum Framework

Development of the MCF aimed to introduce transformative thinking about bringing children and older people’s learning together. It began by considering the characteristics of effective learners within Birth to 5 Matters (Early Years Coalition, 2021), before working towards a definition of personal resilience that could be shared by both children and older people. Drawing on the work of Davies et al. (2019), a vision of care and learning across the lifespan was formed, defined as “an ability to draw on strengths and assets to cope and thrive in all situations whether they relate to relationships, emotions, care or learning” (Ready Generations, 2023). Inspired by the Froebel Trust (2024), Learning and Teaching Scotland (2006), and research by Heslop (2019) and Clark (2022), understanding of the importance of time developed.

Earlier consultation with older people during practice helped in understanding the importance to them of not feeling rushed and being free to use time in ways that allowed them to explore and experiment with the curriculum. Using their feedback and rationale, delivery of the nursery curriculum was slowed down with transitions managed sensitively. This was hugely impactful in allowing children to enjoy flow and follow their own interests in ways that permitted in-the-moment planning. This practice is supported by Clark (2022, p. 123), who stated that “the case is made for a ‘time full’ approach to Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) that can offer a more sustainable and play focused approach to early childhood across generations and communities”, as well as Heslop’s (2019, p. 118) data, which indicated that by “slowing down and having the time, you discover things that you didn’t even know were there”.

The Mirrored Curriculum Framework aims – a sense of shared purpose for child and adult care

From this initial starting point, the MCF has been consistently reviewed and improved following feedback from all stakeholders, for example during staff training and informally with older people and parents. This has enabled experiences for children and older people to be more thoughtfully planned, taking into account individual needs, interests and desires in line with expectations set out in the Early Years Foundation Stage and ambitions for a more person-centred care for older people. It also represents a significant paradigm shift from ‘this is what is available and will be offered to you’ to ‘tell me more about what interests you and how we can work together to understand and meet your needs holistically’. Such a highly personalised approach has been hugely instrumental in building the trust, confidence and engagement of everyone and reflects similar findings to the work of the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (2006).

Ten aims have been developed that provide form and function to the intergenerational curriculum, meeting Ofsted requirements to evidence curriculum intention, implementation and impact (see Table 2). These support Ready Generations’ teaching and learning ambition of providing a broad and balanced curriculum that meets all statutory requirements and is planned in response to children and older people’s interests and needs.

Table 2 The 10 aims of the Mirrored Curriculum Framework (MCF)

| Mirrored Curriculum Framework aims | |

| 1. | Define the features of effective intergenerational communities, allowing for sustained interactions across the stages of life, leveraging the value that generations bring to each other. |

| 2. | Enable psychological safety and ensure effective safeguarding are at the heart of practice. |

| 3. | Ensure everyone is included and diversity and dignity are prized. |

| 4. | Plan learning experiences in well-designed environments that work for all ages. |

| 5. | Promote personal autonomy through learning provocations, opportunities and experiences. |

| 6. | Advance models for learning that move from segregation to integration and favour one strong community of many generations. |

| 7. | Prioritise relationships as an investment in healthy, purposeful living and learning. |

| 8. | Enable a sense of playfulness and encourage active exploration, recognising the centrality of curiosity and the capacity to respond to personal motivations and desires. |

| 9. | Recognise that learning is a creative act and that creativity is a way of being that invites unexpected connections and allows for learning to be seen in new ways. |

| 10. | Use nature and the outdoors to enhance attention, self-discipline, spirituality and responsibility for sustaining natural ecosystems and ultimately the planet. |

Mirrored Curriculum Framework domains

The enhanced focus on the curriculum in the current Early Years Inspection Framework (Ofsted, 2024, paragraph 171) is clear in the expectations about the types of information inspectors will evaluate when assessing the quality of an early years setting. These dovetail with the Care Quality Commission’s (2023) statements for older people’s care:

- Person-centred pedagogy – allocating as much time as necessary to understand what children and older people already know and what underpinning meanings they bring to their learning – for example, motivation, culture, expectations, tradition.

- Curriculum tailored to need – creating interconnected feedback loops that value and encourage deep thinking on achievements and successes whether small or large and support children and older people to notice their own and each other’s contributions and progress.

- Holistic learning experiences – paying close attention to personal identity, resourcefulness and belief, recognising that children and older people can be vulnerable in similar and diverse ways.

- Careful planning – giving in-depth consideration of the skills, knowledge and behaviours needed for effective learning and how to make learning participatory, interesting and engaging.

- Compliance and best practice – ensuring full compliance with statutory requirements.

- Collaborative – bringing professionals together to collaborate and learn from each other, making shared decisions about best practice.

- Understanding and responding to barriers – hearing and understanding concerns or underlying issues that may form barriers to access and engagement.

- Effective assessment models – recognising that formative and summative assessment is an important and integral part of evidence-based processes and provides data about the needs, engagement and learning patterns of both children and older people.

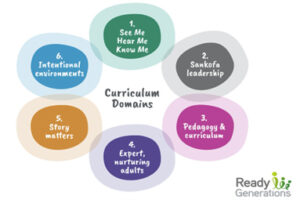

Figure 2 The Mirrored Curriculum Framework domains (Egersdorff and Ludden, 2022)

The MCF’s aims were shaped around six interdependent domains (Figure 2). Each domain presents a way of structuring a particular set of knowledge, skills and understanding to support effective teaching and learning and the highest-quality care and education for all. The concept of mirroring reflects the vision for a curriculum offer that is flexible for all ages, interesting and inviting.

Domain 1 – See Me, Hear Me, Know Me – represents the conscious act of acknowledgement. It reflects a shared responsibility for each other as well as the professional accountability of the educator and carer. It sets the tone for meaningful learning and trusting interactions that value individual uniqueness.

Domain 2 – Sankofa Leadership – introduces deliberate leadership, putting people first and focusing on human-centred design. It stems from the Ghanaian tradition of the Sankofa bird. Sankofa – san (return), ko (go), fa (look, seek and take) – teaches us that we must go back to our roots in order to move forwards. This means we should reach back and gather the best of what our past has to teach us so that we can reach our full potential as we develop and grow: “Sankofa – it is not wrong to go back for that which you have forgotten” (Witness Stones, p. 2023). The importance of allowing our older people to lead and act as wise educators to younger generations is embodied throughout this domain.

Domain 3 – Pedagogy and Curriculum – outlines how an effective curriculum is fundamental to impactful learning. The MCF is compliant with the Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) statutory framework (Department for Education, 2023), which sets out the standards that school and childcare providers in England must meet for the learning, development and care of children from birth to five years of age. Domain 3 builds on the seven EYFS areas of learning. Three of these areas – communication and language; physical development and wellbeing; and personal, social and emotional development and wellbeing – are not only important for children but particularly applicable in supporting older people, particularly those living with dementia and frailty.

The non-statutory guidance provided through the Early Years Coalition’s (2021) three characteristics of effective learning – playing and exploring, active learning, and creating and thinking critically – also supports learning across the ages.

These sit comfortably alongside the commitments outlined in the Care Quality Commission’s (2023) new quality statements. Expressed as ‘we’ statements, they show what is required to provide the highest-quality person-centred care. For example, for the statement ‘learning, improvement and innovation’, the commitments are as follows:

We focus on continuous learning, innovation and improvement across our organisation and the local system. We encourage creative ways of delivering equality of experience, outcome and quality of life for people. We actively contribute to safe, effective practice and research. (Care Quality Commission, 2023, p. 1)

Domain 4 – Expert and Nurturing Adults – considers multi-professional development and the creation of shared learning pathways, whereby professionals from both early education and adult social care are committed to their own development and work together. Shared reflective practice and research are key features of impactful intergenerational approaches. Nurturing adults include older people, many of whom provide rich life experiences and support both children and other older people carefully. They act as responsible educators, supporting and extending interests through ‘freedom with guidance’. This is a Froebelian concept, shaped by Froebel’s belief that education brought freedom (Tovey, 2012). Froebel believed that by helping children to think for themselves, make deliberate choices and follow their own unique interests, they would flourish and successfully face the challenges of life. Heslop’s (2019) research discusses this, while both evaluation and anecdotal feedback from older people reflects their desire to offer this willingly to the nursery children, demonstrating a real commitment to their learning and progress.

Domain 5 – Story Matters – places oracy and storytelling as central components of the curriculum at every level. Effective talk and conversations that are given the time and support to extend thinking and challenge ideas are hugely beneficial to young children as they strive to make sense of the world. The additional dynamic of rich stories from the older generation inspires young children to use their imagination and intuitive creativity. Stories may be formal or informal collaborations, helping people of all ages make sense of new situations, content and experiences and enabling them to remember and do more. By allowing immersion in other people’s stories, key relational skills such as observation, perception and empathy develop (Making Caring Common, 2023).

Domain 6 – Intentional Environments – introduces the concept of intentional environments. These are spaces designed specifically to provide the best possible learning and care experiences. This requires adaptive space that is sensitive to the changing needs of the community. Intentional environments additionally reflect the culture and way of life of the community, such as its habits, values and purpose, while also demonstrating a commitment to future thinking, creativity and innovation.

The Attuned Relationships Model and Mirrored Curriculum Framework – implications for practice

All children and older people should have access to the highest-quality care and learning. If we believe this and strive for this outcome, there is a need to constantly be alert to the rapidly changing world that surrounds both older adults and young children. Current funding arrangements for early education and care make steady improvement difficult to achieve, and the challenges associated with funding and the workforce should not be minimised – they represent significant barriers to consistency and quality.

Table 3 The Mirrored Curriculum Framework (Egersdorff and Ludden, 2022)

| Self | Care | Social | Culture |

| Identity Agency Dignity Determination Autonomy Validation Consciousness Awareness Uniqueness Learning Celebration | Human rights Control Choice Love Affection Belief Intimacy Respect Needs | Independence Interdependence Friendships Relationships Motivation Participation Empathy Perception Value to others Celebration | Inclusive Generous Dignified Kind Equitable Fair Transparent Freedom

|

New directions are possible and there is power in reimagining what quality education and care could look like, regardless of the setting. Since opening the intergenerational nursery in the north of England, where older adults and young children spend many hours in each other’s company, it has been apparent that to succeed with the Ready Generations vision, it is necessary to continually lift heads to look more widely at the issues affecting early childhood development and lifelong physical and mental health. Many fundamental issues – including ageism, racism, exposure to toxins, climate change, poverty, built environments and policy changes – affect all ages and are interdependent. Realising this and placing early years care and education within an interrelated human ecosystem is empowering and exciting. The National Scientific Council on the Developing Child (2023) shares this view of the potential of strengthening community living and paying greater attention to environment and shared spaces. It suggests that re-examining cross-sector policies and associated systems may help to connect the dots of quality care and education for all in new ways by:

- strengthening community assets that support healthy development

- preventing, reducing and/or mitigating environmental conditions that threaten human wellbeing, with particular attention to the most affected communities

- understanding how both assets and threats are built into the body, beginning prenatally and continuing in the early childhood period, and how they result in either a strong or weak foundation for all the learning, behaviour and health that are necessary for a thriving and sustainable society (National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2023, p. 13).

For care and education models set within a home care base, whatever that home care base may look like, it is impossible to separate provision for the child from everything else that is happening within that home context. While Bronfenbrenner (1979) placed an individual at the centre of the human ecosystem and demonstrated how they are affected by a myriad of interconnected systems around them, the authors of this paper recognise that there are similarities between the needs of the older adults and young children in society. Table 3 (above) demonstrates the range of interconnected issues that impact the needs of both children and older people, which prompted the development of the MCF. Recognising this and noticing why it is so important has been central to the positive impacts observed during practice to date.

Conclusion and recommendations

Ready Generations’ developing model of intergenerational integrated early education and care is not groundbreaking. Instead, it is a return to past times, when the expectation was that babies, young children and older people would be cared for in their own home, which often contained three or more generations. In this environment, roles and responsibilities were understood, with the care and nurture of children frequently given by the older generation. It is appreciated that perfection was not always achieved, but there was often reduced isolation and a genuine sense of reciprocity. This remains the way for many nomadic traditions and indigenous people around the world.

However, growing interest in intergenerational models, often for non-familial individuals, is coming at a time when there is a need to look at early care and education and older people’s care through a new lens. Ready Generations’ model of integrated early education and care is in its infancy, and there is a need for deeper understanding and more data collection around the impact of intergenerational practice over time. Learning to date supports the foundational position in the paper about the potential additional value of developing an intergenerational model of educare. The provision of early years education within a care facility has demonstrated significant and, at times, extraordinary outcomes for both children and older people. However, to consistently achieve this aspiration requires deep thinking and ongoing attention to detail. It is not something to implement half-heartedly. Working to build the relationships that allow effective teaching and learning to happen in both planned and spontaneous ways requires time, patience, energy and commitment.

The introduction of bespoke relational and curriculum models, specifically designed to accommodate both children and older people, is a clear shift towards improvement in the structuring, monitoring and evaluation of intergenerational outcomes. It facilitates shared purpose, community and interdependence while supporting professionals to bring together priorities, standards and resources in more impactful ways to be able to argue the efficacy of the approach.

At a systems level, bringing early years and adult social care sectors together has required a sophisticated understanding of the challenges of harmonious and effective partnership working. This has involved courage, patience, constant listening, cooperation and mutual respect, as well as an acknowledgement that together we are stronger and better at what we do – we are authentically interdependent.

Moving forwards, it will be important to identify and evidence the qualities, components and characteristics of effective practice within the context of building a more humane and adaptable form of regenerative care and education. A full evaluation of the ARM and the MCF, undertaken by university researchers, would be supportive of continuous, critical reflection on practice. Strong leadership and workforce capability will be critical in bringing this new vision to life and overseeing meaningful transformation. Softer skills such as compassion, reciprocity, empathy and self-awareness will feature more strongly, making role-specific skills appear more restrictive and limiting. Cross-sector leadership will need to recognise and understand the interrelated factors of human ecosystems that do not delineate people by age or circumstance, but view care and education needs inclusively within the broader context of families and communities.

Funding

There was no funding for the development of the frameworks presented in this paper.

Declaration of authorship and no conflict of interest

This is original work. The manuscript has not been submitted or published previously elsewhere, including under a different title. There are no known conflicts of interest associated with the paper. The Mirrored Curriculum Framework and Attuned Relationships Model were developed by two of the authors following their engagement in prior research, from their reading and from significant experience in professional practice and leadership. Two authors have engaged with Ready Generations in research alongside the development of these frameworks. Further research will follow.

References

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979) The ecology of human development: experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Care Quality Commission (2023) Key questions and quality statements. Available at: https://www.cqc.org.uk/assessment/quality-statements (Accessed: October 2023).

Cassidy, J. (2021) Intergenerational child and elder care: supporting improved outcomes for communities. Available at: https://www.churchillfellowship.org/ideas-experts/fellows-directory/jacqueline-cassidy/ (Accessed: September 2023).

Center on the Developing Child (2021) 3 principles to improve outcomes for children and families. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University.

Centre for Ageing Better (2022) The state of ageing report. London: Centre for Ageing Better.

Child Poverty Action Group (2017) The austerity generation.

Child Poverty Action Group (2020) Post-Covid policy: child poverty social security and housing.

Clark, A. (2022) Slow knowledge and the unhurried child: time for slow pedagogies in early childhood education. Oxfordshire: Routledge.

Cliffe, J. and Solvason, C. (2023) ‘What is it that we still don’t get? – Relational pedagogy and why relationships and connections matter in early childhood’, Power and Education, 15(3), pp. 259–273.

Crisp, N. (2020) Health is made at home, hospitals are for repairs. Salus Global Knowledge Exchange.

CSI Market Intelligence (2022) Say hello wave goodbye. Available at: https://csi-marketintelligence.co.uk/shwg.html (Accessed: October 2023).

Davies, A.R., Grey, C.N.B., Homolova, L. and Bellis, M.A. (2019) Resilience: understanding the interdependence between individuals and communities. Cardiff: Public Health Wales NHS Trust.

Department for Education (2023) Statutory framework for the early years foundation stage. Crown Copyright.

Department for Education (2023a) Early years foundation stage profile handbook. Crown Copyright.

Durrant, A., Rhodes, G. and Young, D. (eds) (2011) Getting started with university-level work based learning. Middlesex: University Press.

Early Years Coalition (2021) Birth to 5 matters: non-statutory guidance for the Early Years Foundation Stage. Available at: https://birthto5matters.org.uk/ (Accessed: October 2023).

Egersdorff, S. and Ludden, L. (2022) The attuned relationships model. Unpublished.

Egersdorff, S. and Ludden, L. (2022a) The mirrored curriculum framework. Unpublished.

Equality and Human Rights Commission (1998) The Human Rights Act. Available at: https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/human-rights/human-rights-act#:~:text=The%20Human%20Rights%20Act%201998,the%20UK%20in%20October%202000 (Accessed: September 2023).

Fazackerley, A. (2023) ‘Thousands of Covid generation under-fives excluded from schools in England’, The Guardian, 7 October. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/education/2023/oct/07/covid-generation-under-fives-excluded-from-schools-in-england (Accessed: October 2023).

Fitzpatrick, A. and Halpenny, A.M. (2022) ‘Intergenerational learning as a pedagogical strategy in early childhood education services: perspectives from an Irish study’, European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 31(4), pp. 512–528.

Froebel Trust (2024) Inspiring early learning. Available at: https://www.froebel.org.uk/ (Accessed: September 2023).

Gawande, A. (2014) Being mortal. London: Profile Books Ltd.

Generations Working Together (2024) Global intergenerational week. Available at: https://generationsworkingtogether.org/global-intergenerational-week#:~:text=Global%20Intergenerational%20Week%20returns%20for%202024!&text=The%20campaign%20will%20run%2024,this%20webpage%20for%20regular%20updates (Accessed: December 2023).

Heslop, A.K. (2019) Intergenerational practice: a participatory action research study investigating the inclusion of older adults in the lives of young children within an urban ‘forest school’ environment. EdD thesis. University of Sheffield.

Heslop, K. and Caes, L. (under review) ‘Born4Life: creating and supporting meaningful, authentic intergenerational experiences’, Journal of Intergenerational Relationships.

Highet, G. (1950) The art of teaching. New York: Vintage Books.

Hwang, V.W. (2012) The seven commandments of Silicon Valley. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/victorhwang/2012/09/24/the-seven-commandments-of-silicon-valley/ (Accessed: September 2023).

Joseph Rowntree Foundation (2006) Making user involvement work: supporting service user networking and knowledge. Available at: https://www.jrf.org.uk/making-user-involvement-work-supporting-service-user-networking-and-knowledge (Accessed: September 2023).

Kindred Squared (2023) 2022 school readiness survey. Available at: https://kindredsquared.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Kindred-Squared-School-Readiness-Report.pdf (Accessed: 10 May 2023).

Learning and Teaching Scotland (2006) The Reggio Emilia approach to early years education. Available at: https://education.gov.scot/resources/the-reggio-emilia-approach-to-early-years-education/ (Accessed: November 2023).

Local Government Association (2020) Towards a sustainable adult social care and support system. Local Government Association.

Major, L.E. and Briant, E. (2023) Equity in education. London: John Catt Educational: Hodder Education.

Making Caring Common (2023) How to use stories to help kids develop empathy. Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Marmot, M., Allen, J., Boyce, T., Goldblatt, P. and Morrison, J. (2020) Health equity in England: the Marmot Review 10 years on. Institute of Health Equity. Available at: https://www.health.org.uk/publications/reports/the-marmot-review-10-years-on (Accessed: October 2023).

Marmot, M., Allen, J., Goldblatt, P., Boyce, T., McNeish, D., Grady, M. and Geddes, B. (2010) Fair society, healthy lives (The Marmot Review). Available at: https://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/fair-society-healthy-lives-the-marmot-review/fair-society-healthy-lives-full-report-pdf.pdf (Accessed: September 2023).

Mulholland, K. (2022) Moving forwards, making a difference. Available at: https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/news/eef-blog-moving-forwards-making-a-difference (Accessed: October 2023).

National Day Nurseries Association (2023) Nursery closure rates up fifty per cent on last year. Available at: https://ndna.org.uk/news/nursery-closure-rates-up-fifty-per-cent-on-last-year/ (Accessed: November 2023).

National Scientific Council on the Developing Child (2023) Place matters: the environment we create shapes the foundations of healthy development. Harvard University: Center on the Developing Child.

NHS Confederation (2023) Adult social care and the NHS: two sides of a coin. NHS Confederation.

Ofsted (2022) Education recovery in schools: spring 2022. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/education-recovery-in-schools-spring-2022 (Accessed: October 2023).

Ofsted (2024) Early years inspection handbook. Crown Copyright.

Pratt, C. (1948) I learn from children. New York: Harper & Row.

Ready Generations (2023) Visions of us – year one impact report. Available at: https://www.nurseryinbelong.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/NURSERY-IMPACT-REPORT-YEAR-ONE-Sept-2023_web_singlepgs.pdf (Accessed: September 2023).

The King’s Fund (2019) Public satisfaction with the NHS and social care in 2019. The King’s Fund and Nuffield Trust.

The UK Women’s Budget Group (2021) Access to childcare in Great Britain. Available at: https://wbg.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Briefing-Childcare-FINAL-version.pdf (Accessed: September 2023).

Tovey, H. (2012) Bringing the Froebel approach to your early years practice. London: David Fulton Publishers.

UK Parliament (2021) Impact of Covid-19 on early childhood education and care.

United Nations (1989) Convention on the rights of the child: treaty no. 27531. United Nations Treaty Series 1577.

United Nations (1991) Principles for older persons. General Assembly resolution 46/91.

Virdi, A. (2023) Nursery closures increase by half in one year. London: Children and Young People Now: Mark Allen Group.

Ward, T. and Brown, M. (2004) ‘The good lives model and conceptual issues in offender rehabilitation’, Psychology, Crime and Law, 10(3), pp. 243–257.

Witness Stones (2023) The Sankofa bird. Liberty Legacy Memorial. Available at: https://www.libertylegacymemorial.org/sankofabird (Accessed: October 2023).

Related articles

Front matter and content page: Norland Educare Research Journal

The Norland Educare Research Journal is an international double-blind peer-reviewed journal, published annually, online only. It is an open access journal, offering free-of-charge publication to researchers and authors, and free...

Editorial — Revisioning and reforming educare in the 21st century: the synergetic confluence of professional innovative practices and scientific evidence

This issue of the journal presents a collection of papers which bring to the fore critical issues about young children’s educare. In an interview conducted by Janet Rose, the Principal...

Useful links and information for the Norland Educare Research Journal

About the journal

Read more about the journalEditorial board

View our editorial boardJournal policies and ethics

View journal policies and ethicsInformation for readers

View information for readersInformation for authors

View information for authorsCall for papers

View call for papersTerms and conditions

View terms and conditions

Translate this page